Just Transition and Emerging Markets: Risk Assessment

tum3123

Author: Saskia Kort-Chick, Markus Schneider

Understanding the social risks posed by climate change requires discipline, nuance and a systematic approach.

The concept of a “just transition” has become entrenched among responsible investors concerned about the economic consequences of their social environment. The risks that countries face when transitioning from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources. These risks are particularly high in emerging markets (EM). How can investors systematically measure this?

Simply put, a just transition means transitioning away from fossil fuels, mindful of the economic impacts and in a way that does not destroy the social fabric of the economy.

The consequences of a mismanaged transition can be severe in countries exporting coal or oil, especially those with relatively undiversified economies. As demand for these raw materials declines, the country may face more severe transition risks. The government may face fiscal and debt problems that strain its sovereign credit. evaluation. Worse, economic deprivation and civil unrest can lead to political instability and even regime change.

In developing a systematic approach to assessing these risks, it is helpful to focus on the sector that is at the center of most transition strategies: energy production, and particularly coal (the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel). This has the added advantage that coal transitions already underway, such as in Germany, Poland, the UK and the US, provide policy lessons and examples of pitfalls to avoid. This can be a useful lens for analyzing how emerging markets are managing their just transitions.

Policy Lessons: Learning from Experience

For example, policy lessons demonstrate the need for a holistic, integrated government planning process that focuses on worker well-being, economic diversification, and social and environmental conservation. Without the help and commitment of national and local governments, it is difficult to achieve a just transition.

Planning is essential, but in reality, macroeconomic prerequisites such as existing levels of industrialization and access to infrastructure are critical to the government’s efforts to diversify coal regions. Additionally, general labor market protections and social security networks are critical to protecting workers during the transition to alternative employment. In that context, the location of coal mines is also important. This is because diversification in very remote areas (where many EM mines are located) is difficult.

Relative transition risks and specific vulnerabilities

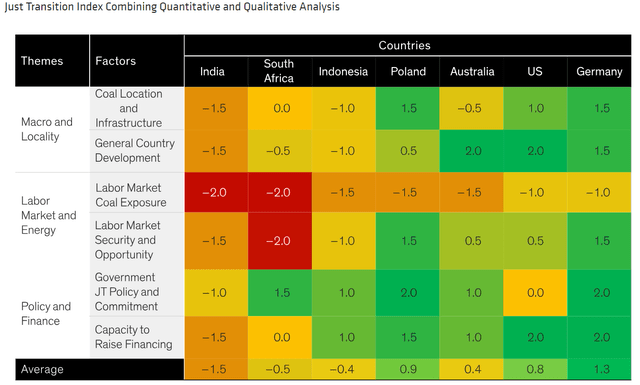

Building on past policy lessons, we created the Just Transition Index (JTI), which scores countries across a range of key indicators. The score is intended to capture a country’s overall level of macroeconomic development, mine location, labor and energy market composition, government policy commitment to a just transition, and financing capacity.

Some indicators are relatively easy to measure quantitatively (e.g. a country’s level of development, labor market exposure to coal, government budget capacity, etc.), while others (e.g. coal mine location, government willingness to reform) are more difficult to quantify. Yes. .

For this reason, we chose a qualitative index that scores each country from -2 to 2. where the lowest number represents the greatest risk (Denote). JTI provides guidance on a country’s overall relative risk (included in the score average) as well as its specific vulnerabilities (individual factor scores).

Country Exposure to Coal Transition Risks: Heatmap

For illustrative purposes only. Current analysis does not guarantee future results. Not all countries are displayed. As of February 28, 2024 (Source: AllianceBernstein (AB))

But the value of this approach to investors is not just systemic. Primary qualitative research is important to understand the nuances of transition risk.

Prerequisites are key variables

As mentioned earlier, EM is particularly exposed. For example, labor rights and opportunities in emerging countries tend to be less extensive than in developed countries. In India, Indonesia and China, coal production is located far from urban centers, limiting the extent to which coal-dependent populations can be transitioned to alternative employment without displacement costs or disruption.

Poland demonstrates this well. Our country began moving away from coal about 30 years ago. The transition wasn’t smooth, but it worked well in one key respect. Many of Poland’s coal mining areas are co-located with major industries such as car manufacturers and information and communication technology service providers.

In Indonesia the situation is different. Coal production is concentrated in South Kalimantan and Sumatra and accounts for 35% of East Kalimantan’s GDP. The region is far from the islands of Java and Bali, which account for 60% of Indonesia’s population and GDP. However, these problems could be alleviated through plans to relocate Indonesia’s capital (now Jakarta, on Java’s northwest coast) to East Kalimantan.

A practical and potentially rewarding approach

Other policy lessons reflected in these cases are that stakeholder expectations must be managed (as Poland shows, transitions can take decades) and strategies must be holistic rather than piecemeal. (In Poland, funding and other support from the European Union helped coordinate the restructuring of the mining sector and the creation of new jobs.)

A just transition is a huge, complex and long-term challenge in emerging markets and elsewhere. A systematic approach based on solid primary qualitative research offers investors a practical and potentially rewarding way to engage.

The authors would like to thank Roxanne Low, ESG Analyst, and Kristian Tonev, Associate Fixed Income from AB’s Responsible Investment team for their contributions to the research.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trading recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of the entire AB Portfolio Management team. Views may change over time.

original post

Editor’s note: The summary bullet points for this article were selected by Seeking Alpha editors..