Bitcoin is reshaping where cities and data centers will rise, competing for wasted energy rather than cheap labor.

For two centuries, factories chased cheap labor and crowded ports. Today, as miners travel to windswept plateaus and hydraulic drainage ditches, they ask simpler questions: Where are the cheapest wasted watts?

When computing can move energy away from people, the map tilts.

Heavy industry has always sought cheap energy, but it still needs bodies and ships. The novelty of Bitcoin (BTC) is that labor, logistics, and physical products are completely taken out of the siting equation.

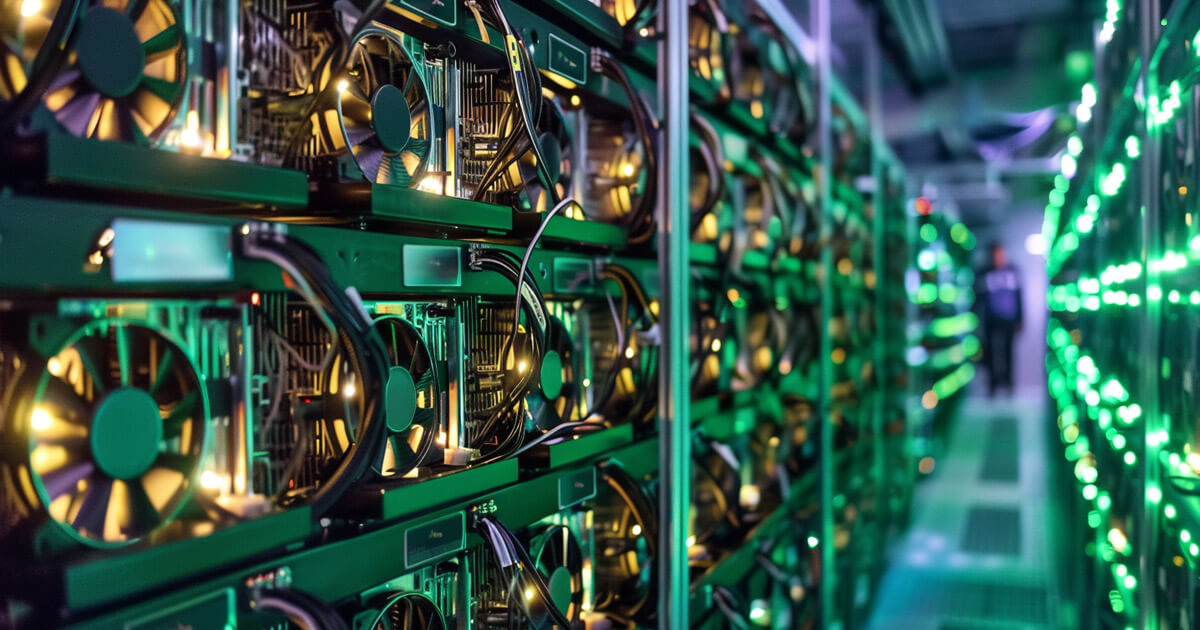

A mining plant may consist of one warehouse, 12 employees, an ASIC stack, and a fiber line. The output is a pure block reward, not a bulky commodity that must be shipped. This allows miners to connect to truly stranded or curtailed energy that is inaccessible from traditional plants and can rush in when policy or prices change.

Bitcoin is not the first energy-seeking industry, but it is the first large-scale industry to make a default position bid: “Give me the cheapest wasted megawatt and I will show up,” with labor largely irrelevant.

Retrenchment creates new subsidies

CAISO has scaled back utility-scale solar and wind by about 3.4 TWh in 2023, about 30% more than in 2022, and by more than 2.4 TWh in the first half of 2024 alone as midday generation routinely exceeds demand and transmission limits.

Node prices are often negative. Outages are expensive, so generators want to pay the grid and still get renewable tax credits.

Miners appear as strange new bidders. Soluna builds modular data centers in wind and solar projects that absorb power that the grid cannot absorb. Riots in Texas have reduced power supplies during peak demand, resulting in about $71 million in power credits in 2023, often more than offsetting the BTC to be mined.

In 2024, Bitcoin mining companies converted shrinks into tens of millions of dollars of credits, and are on track to beat 2025, with more than $46 million in credits booked in the first three quarters alone.

A 2023 paper in Resources and Energy Economics models Bitcoin demand in ERCOT and finds that not only can miners increase renewable capacity, but they can also increase emissions, and many of the downsides are mitigated if miners operate as demand-responsive resources.

Curtailment and negative pricing are de facto subsidies to everyone who knows exactly where and when power is cheapest, and mining is designed to do this.

Hashrate moves faster than factories.

Miners migrated seasonally within China, chasing cheap monsoon hydropower in Sichuan province and then moving to coal regions like Xinjiang when the rains stopped.

When Beijing cracked down in 2021, that mobility spread around the world. The United States’ hashrate share jumped from single digits to about 38% by early 2022, while Kazakhstan’s share soared to about 18% as miners lifted entire farms and replanted them into the coal-rich grid.

Over the past year, US-based mining pools have mined over 41% of Bitcoin blocks.

Reuters recently reported that China’s share has quietly rebounded to around 14%, concentrated in areas with surplus power.

ASICs are the size of containers and produce virtual assets that depreciate after 2-3 years and are the same no matter where they are located. This allows hashrate to bounce across borders in ways that steel mills or AI campuses cannot.

Miners could make the switch within months if Kentucky exempts mined electricity from sales taxes or Bhutan offers long-term hydropower contracts.

The line between programmable knobs and wasted power

ERCOT treats certain large loads as “controllable load resources” that can be reduced within seconds to stabilize frequencies.

Lancium and other mining facilities brand themselves as CLR, promising almost immediate reductions when prices spike or reserves run low. Riot’s July and August 2023 reports read like a grid services earnings release, with millions of dollars in power and demand response credits booked during a heatwave, along with far fewer self-mined coins.

The OECD and national regulators are now discussing Bitcoin as a flexible load that could deepen renewable penetration or rule out other uses.

Miners bid for interruptible power at the lowest rates, grid operators get a buffer they can call on when supply is tight, and the grid absorbs more renewable capacity without overbuilding transmission.

Bhutan’s sovereign wealth fund and Bitdeer are building at least 100 MW of mining facilities powered by hydroelectric power, monetizing excess hydropower and exporting “clean” coins as part of a $500 million green cryptocurrency initiative. Government officials have reportedly been using cryptocurrency profits to pay government salaries.

In West Texas, wind and solar power facilities face transmission bottlenecks, reducing transmission rates and driving down prices.

This is where many U.S. miners have signed PPAs with renewable power plants to secure capacity that the grid can’t always absorb. Crusoe Energy provides modular generators and ASICs for remote wells using associated gases that can be combusted.

A cluster of miners with three overlapping conditions: energy is cheap or stranded, transmission is limited, and local policies either welcome it or ignore it. Bitcoin mining can reach sites that labor-intensive industries could never reach.

AI adopts a playbook that has limitations.

The U.S. Secretary of Energy’s Energy Advisory Council warned that AI-driven data center demand could add tens of gigawatts of new load by 2024. It emphasized the need for flexible demand and new location models.

Companies like Soluna are now pitching “modular green computing,” switching between digital assets and other cloud workloads to monetize reduced wind and solar power.

China’s new underwater data center outside Shanghai operates about 24 MW and relies almost entirely on offshore wind and seawater cooling.

Friction comes from latency and uptime SLAs. Bitcoin miners can endure hours of downtime and seconds of network lag.

AI inference endpoints that provide real-time queries cannot. This will keep Tier 1 AI workloads near fiber hubs and major metropolitan areas, but training execution and batch inference are already candidates for energy-rich remote sites.

El Salvador’s proposed Bitcoin City would be a tax haven city at the foot of a volcano, where Bitcoin mining would be powered by geothermal power and Bitcoin-backed bonds would fund both the city and miners.

Whether it is built or not, it shows that the government is putting ‘energy + machines’ as the anchor rather than labor. The data center boom in the upper Midwest and Great Lakes region is attracting hyperscalers with cheap power and water despite a limited local workforce.

The mining campuses that support Bhutan’s hydroelectric power are located far from major cities.

Citizen fabric is thin. Hundreds of skilled workers service racks and substations. Tax revenues flow, but jobs are created per megawatt hour. Local opposition is focused on noise and heat, not labor competition.

By 2035, clusters of power plants, substations, fiber optics, and hundreds of workers define a “city,” becoming plausible machine-first zones with human settlement secondary.

Increase profits through heat reuse

British Columbia’s MintGreen claims it can replace natural gas boilers by feeding immersion-cooled mine heat into urban district heating networks. Kryptovault in Norway converts mining heat into dry logs and seaweed.

MARA ran a pilot project in Finland to provide a high-temperature source for a 2 MW mining facility inside a heating plant for its biomass or gas needs.

Miners who pay the lowest power rates can also sell waste heat, operating two revenue streams from the same energy input. This makes cold climate regions with district heating needs newly attractive.

Kentucky’s HB 230 exempts electricity used in commercial cryptocurrency mining from state sales and use taxes.

Supporters acknowledge that the industry creates few jobs relative to the size of the power subsidies. Bitdeer’s partnership with Bhutan includes sovereign hydropower, regulatory support and $500 million in funding.

El Salvador packaged its geothermal plans and Bitcoin City with legal tender status, tax breaks, and preferential access to volcanic geothermal energy.

The policy toolkit includes tax exemptions on electricity and hardware, rapid interconnection, long-term PPAs for power curtailment and, in some cases, sovereign balance sheet or legal tender experiments.

Jurisdictions compete to provide the cheapest and most reliable flow of electrons with the fewest acceptable obstacles.

What’s at stake?

For two centuries, an industrial landscape optimized for the movement of raw materials and finished products through ports and rail lines has had cheap labor and market access as co-drivers.

The Bitcoin mining boom is the first time a global, capital-intensive industry has emerged where the product is fundamentally digital and the main constraint is energy prices.

This shows where the world’s “wasted watts” live and how much governments are willing to pay to convert those watts into hash through tax breaks, interconnection priorities, and political capital.

If AI and general computing adopt the same mobility, the map of future data centers will be less about cheap people’s homes and more about stranded electrons, cool water, and quiet. Shrinking edges may be erased due to transfer expansion.

The policy reversal could halt billions of dollars in capital spending. The latency requirements of AI can limit the amount of workloads that can be migrated. And the commodity cycle could completely collapse the hashrate economy.

But the direction is visible. Bhutan generates revenue from hydropower through hashish. Texas pays miners to stop mining during heat waves.

Kentucky exempts mining electricity from taxes. Chinese miners are quietly rebooting in provinces with power surpluses. This is a jurisdiction that is rewriting bidding rules for compute-intensive industries.

If the industrial age was organized around hands at the port, the computing age may be organized around watts at the edge. Bitcoin is just the first mover, revealing where the map already wants to be torn apart.