How Miners Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love JPEG

This article was published in Bitcoin Magazine. “The inscription problem”. click here To get an annual Bitcoin Magazine subscription.

Click here to download a PDF of this article.

Ordinal numbers have been a polarizing phenomenon in most every subcommunity of Bitcoin, except miners.

The rapid rise of the new Bitcoin-based NFT standard has dominated the discourse for months, with Ordinals flooding block space and driving transaction fees to multi-year highs. According to critics, these transactions are, at worst, an attack on Bitcoin that pollutes the sanctity of scarce block space. At best, it’s just a shitcoin, a gambler’s toy belonging to a casino chain like Ethereum.

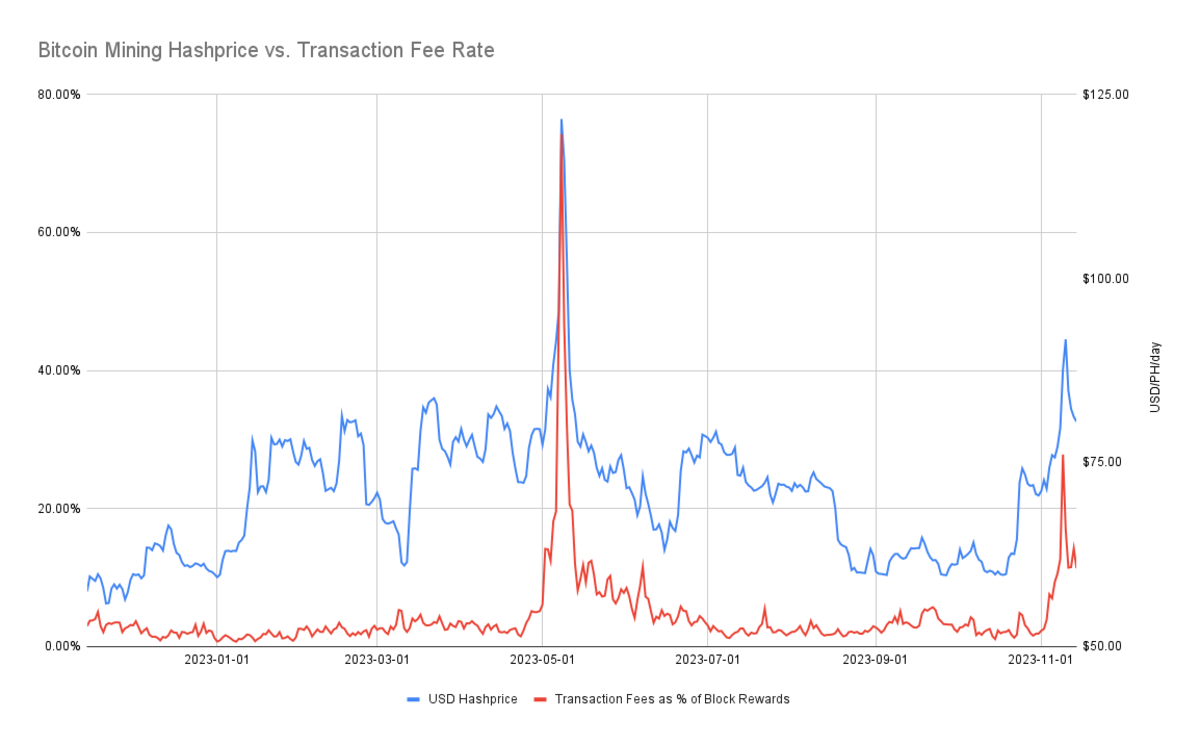

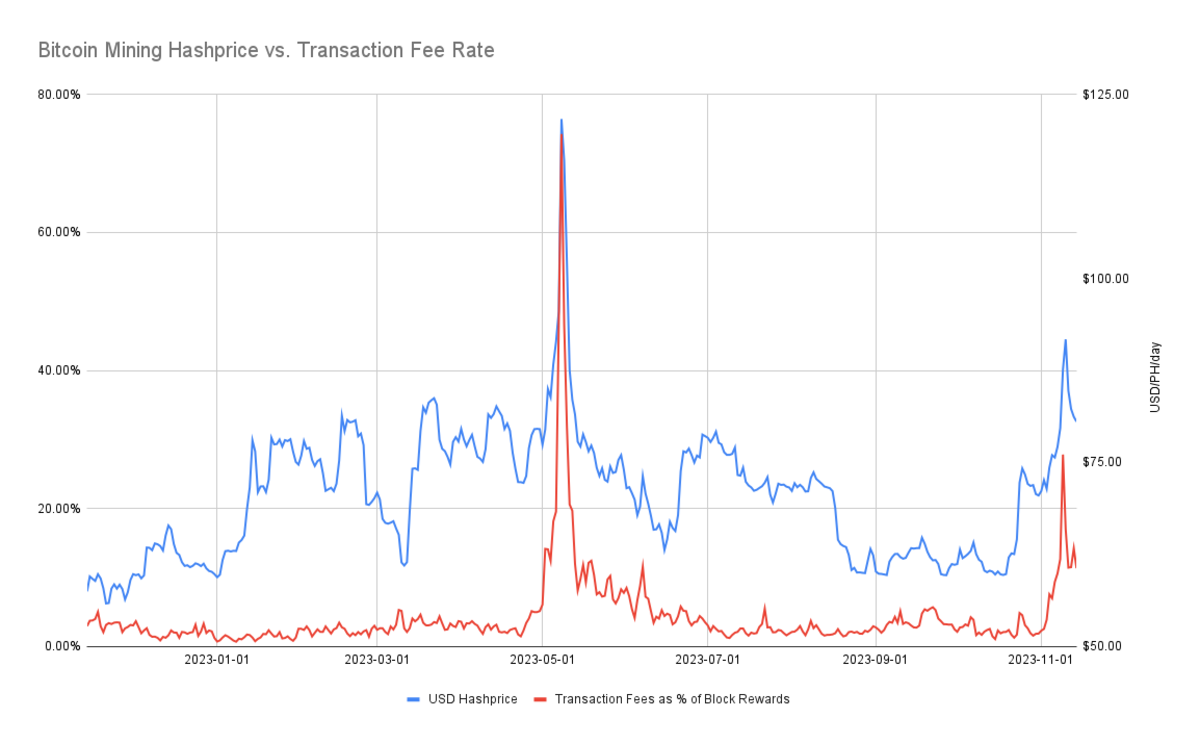

Well, miners don’t care if it’s a shitcoin. They didn’t care much about making money, and Ordinals gave them a boost in profits at a time when mining revenues were at an all-time low. Too many miners accepted ordinal/inscription, or at least took an ambivalent stance. That’s because it’s given a much-needed boost to Bitcoin mining profitability at a time when many miners were barely breaking even or unprofitable.

Hashprice measures the amount of USD (or BTC) a miner can earn in hashrate units (e.g. $80/PH/day, from a miner with a 1 petahash mining rig (roughly equivalent to 10 next-generation ASICs) For example, S19j Pro can earn you $80 per day.

Ordinals, a dark horse technological development that few could have predicted last year given its positive impact on hash prices, has found itself at the center of discussions about Bitcoin mining economics. This is a discussion more closely related to each block that brings us closer to Bitcoin’s fourth block. Subsidy half-life.

I’m not writing this to evangelize anyone into becoming a lover of Ordinals. I don’t really understand the appeal. However, I think this is important in the context of Bitcoin’s block subsidy being tapered off. It is therefore worth studying to understand how this will impact block space and mining economics, and what developments like this could mean for a future where miners survive alone. About transaction fees.

Anyway WTF is an ordinal number?

In NFT terminology, people use Ordinal and Inscription interchangeably, but the individual terms refer to two different aspects of the NFT standard.

While an inscription is a work of art or digital media, an ordinal number is technically a number prescribed to an inscription to indicate its position in the grand scheme of all other inscriptions. Another way to look at this is that the inscription itself is an NFT, while the ordinal numbers are the numbers used to identify the individual inscriptions.

The data for each inscription is in a separate witness section of the transaction. So, unlike other NFT standards, the actual artwork, digital media or data is uploaded directly to Bitcoin’s blockchain. Because Inscriptions are completely on-chain, they benefit from the immutability of the blockchain and can therefore be argued to be the purest form of NFT.

Not all inscriptions are created equal

Understanding that the inscriptions are actual on-chain data makes us understand the criticism and concerns of detractors. With so many NFT degens engraving monkey JPEGs and dick butts and God-knows-what else on chains, this drives out economic (and potentially necessary) transactions.

This concern is further compounded by the fact that random data for each inscription benefits from a transaction fee discount. As a scalability measure, Bitcoin’s Segregated Witness upgrade modified the transaction structure so that witness data for the private key signature and public key are moved from the transaction hash field to other parts of the block. Bitcoin discounts SegWit data, so the transaction fee required for a transaction is fewer satoshis per byte. Random data about the inscription is in the SegWit field of the transaction, so you can get a SegWit discount. Cue the pitchfork.

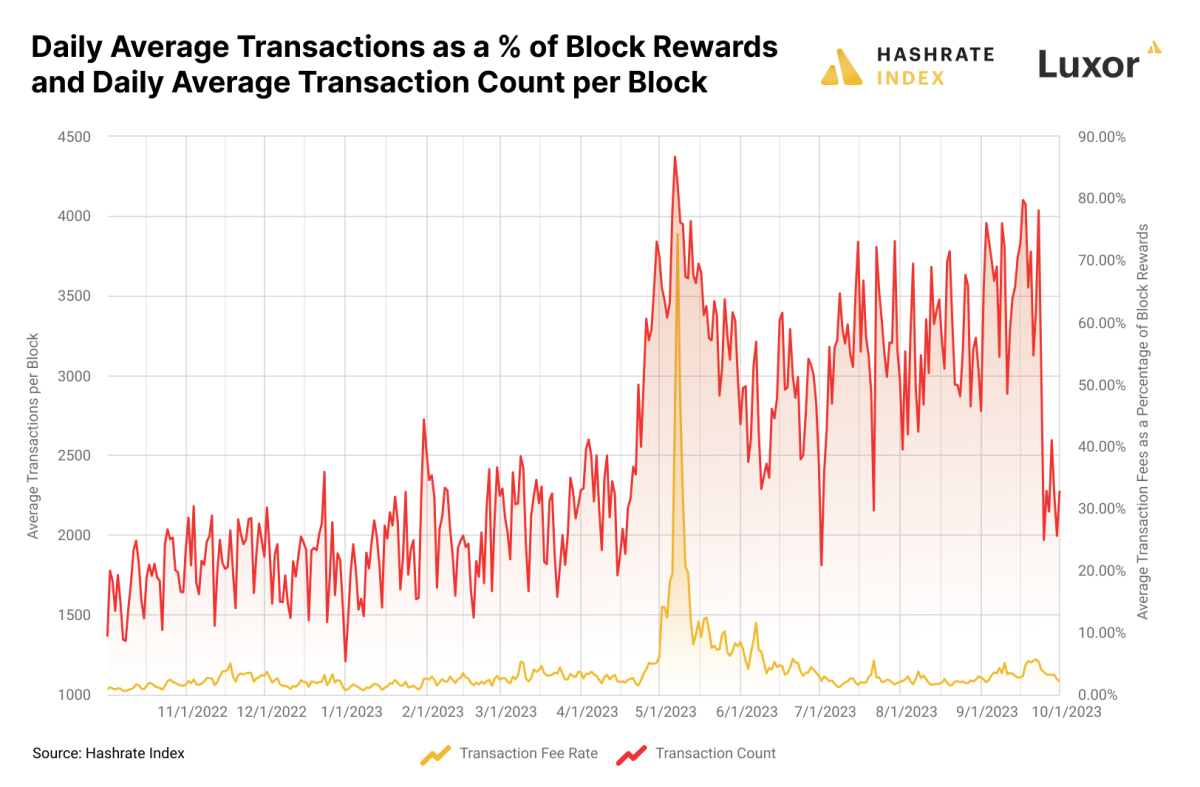

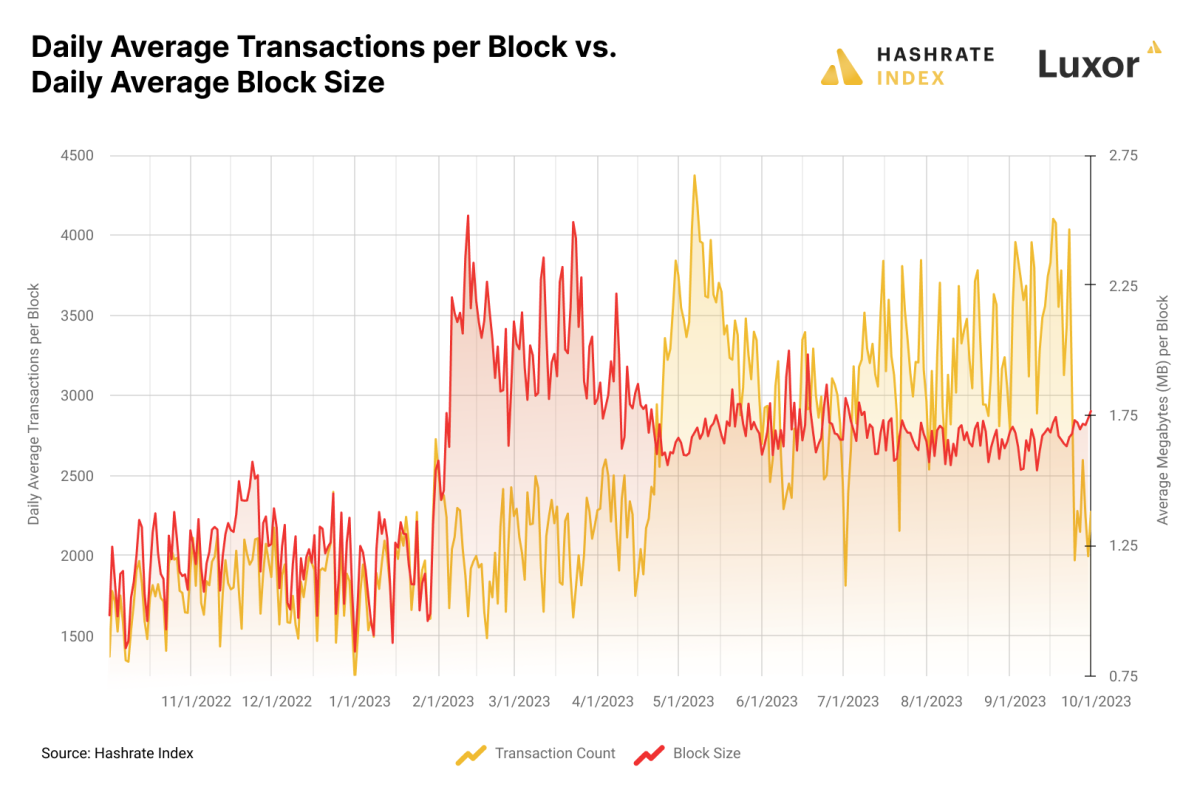

This discount is why transaction fees did not increase meaningfully in February/March/April despite the first wave of image-based inscriptions clogging up block space. Block sizes swelled when trendsetting recordists flushed the blockchain with thousands of JPEGs for their first collection of inscriptions, all of which benefited from SegWit’s 4:1 data discount compared to regular transactions. Perhaps counterintuitively, it was only when the data-intensive text-based inscriptions of BRC-20 tokens became the most popular inscription type that transaction fees soared.

The so-called BRC-20 (Ethereum’s own agreement on ERC-20 token standard) is a loose form of token. I say loosely because it is actually the ordinal number of the series defined by Bitcoin’s OP_CODE function. Here, each “token” itself is an OP_CODE transaction that defines the token’s position in a particular BRC-20 series. It goes like this: Someone (someone only God knows) publishes an OP_CODE transaction that defines the maximum supply of a token series, its ticker, and its issuance limit per transaction. Once released, anyone with the technical know-how can issue a series of tokens.

These OP_CODE transactions do not benefit from SegWit’s data discounts and therefore cost much more than image-based inscriptions. However, there are also features that image inscriptions do not have. It is this issuance feature that provides an Ethereum NFT-like incentive to collect these inscriptions. Ethereum NFT series typically have minting contracts that allow anyone to interact with the contract to create new NFTs in the series. This is part, but not all, of the appeal. Minting an NFT is like opening a digital pack of Pokemon/Baseball/Magic: The Gathering cards. Maybe the next card will have a rare one!

And while you won’t necessarily have the opportunity to mint a rare BRC-20 (since they’re all the same), you will have the opportunity to mint multiple NFTs from a popular new series. I don’t know why you care about having ORDI/CUMY/RATS #1 or #100 etc. Perhaps this is the best expression of Bitcoin’s bigger fool theory. But it is true. The minting incentive for BRC-20 triggered the biggest wave of Bitcoin trading activity.

Through the fee war and the fact that these NFTs do not benefit from the SegWit discount, BRC-20 has created a veritable fee feast for Bitcoin miners, but not exactly in the way you might think.

Quantifying Transaction Fee Collateral Damage

Most of the 2023 transaction fee increases did not come directly from ordinal-related fees. This comes from indirect fee pressure on other transactions.

As of November 12, 2023, miners have received $70.3 million in fees from Ordinals, according to data from independent analyst Data Always’ Dune dashboard. Although it may seem big, this is only 19.4% of the total transaction fees of $368.2 million miners have earned since Inscription launched on December 14, 2022. Looking at this further, there were 40.2 million non-written transactions, or 30%. So Epitaph accounted for a third of last year’s trading volume, but only a fifth of total commissions.

As for other fees, many of them are the result of indirect fee pressure from inscriptions. That is, it is not a fee directly from Inscription itself, but rather a fee due to the pressure Inscription puts on the average transaction fee required to clear a Bitcoin transaction. Within a reasonable time.

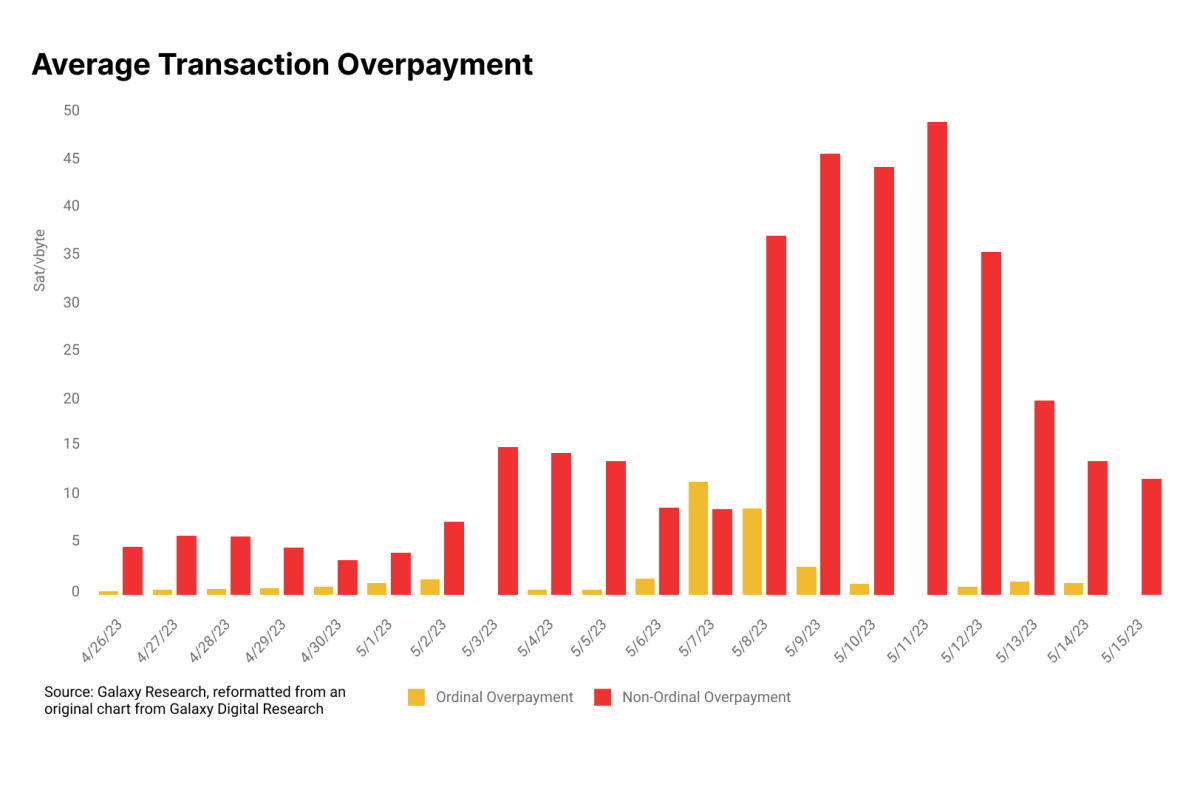

Galaxy Digital Research examines these dynamics in a report titled “Bitcoin Inscriptions & Ordinals: A Maturing Ecosystem.” The memory pool has become crowded due to rampant inscription activity. This is especially true during the BRC-20 minting event. First-come-first-served minting incentivizes bidding wars, as registrants are the first to mint the series. This raises the floor for average trading fees and, as Galaxy Digital Research points out, leads to trading fee “overpayments” from a variety of traders. They define overpayment as the fee for a block that is greater than the median transaction fee for that block. For typical transactions, these overpayments may be due to the wallet or exchange’s transaction fee estimator, or the average user’s ignorance of transaction fee structures and dynamics. Some users may need to expedite transactions for various reasons, which may result in overpayments. For inscription trading, Galaxy Digital Research found that “voluntary overpayments” were common during periods of high activity and popular inscription mints.

This chart quantifies overpayments for inscription transactions and all other transactions to illustrate the dynamics that Galaxy Digital Research explains in its report. When Bitcoin’s mempool experienced a backlog in April and May, which was by far the most active period of Inscription activity, most of the transaction fees during this period actually came from user overpayments for financial transactions, not from Inscription itself. These users can make it easier for themselves by not using the trading fee estimators built into wallets and exchanges.

blessing and curse

The epitaph is both a blessing and a curse. While this is a godsend for miners, it can be a headache for other Bitcoin users, especially those who need to send transactions on the network every day.

In other words, Blockspace is an open market. So I don’t have to like Ordinals to recognize that it’s not my place to monitor other people’s spending. Nor is it my role to censor transactions that pay for block space in a free market. After all, this is one of the keys to permissionless blockchains. That means making deals that other people don’t want to make.

This article was published in Bitcoin Magazine. “The inscription problem”. click here To get an annual Bitcoin Magazine subscription.

Click here to download a PDF of this article.

Source: https://bitcoinmagazine.com/markets/how-miners-learned-to-stop-worrying-and-love-the-jpeg-