The 1.x Files: The State of Stateless Ethereum

In the last edition of The 1.x files, we did a quick re-cap of where the Eth 1.x research initiative came from, what’s at stake, and what some possible solutions are. We ended with the concept of stateless ethereum, and left a more detailed examination of the stateless client for this post.

Stateless is the new direction of Eth 1.x research, so we’re going to do a pretty deep dive and get a real sense of the challenges and possibilities that are expected on the road ahead. For those that want to dive even deeper, I’ll do my best to link to more verbose resources whenever possible.

The State of Stateless Ethereum

To see where we’re going, we must first understand where we are with the concept of ‘state’. When we say ‘state’, it’s in the sense of “a state of affairs”.

The complete ‘state’ of Ethereum describes the current status of all accounts and balances, as well as the collective memories of all smart contracts deployed and running in the EVM. Every finalized block in the chain has one and only one state, which is agreed upon by all participants in the network. That state is changed and updated with each new block that is added to the chain.

In the context of Eth 1.x research, it’s important not just to know what state is, but how it’s represented in both the protocol (as defined in the yellow paper), and in most client implementations (e.g. geth, parity, trinity, besu, etc.).

Give it a trie

The data structure used in Ethereum is called a Merkle-Patricia Trie. Fun fact: ‘Trie’ is originally taken from the word ‘retrieval’, but most people pronounce it as ‘try’ to distinguish it from ‘tree’ when speaking. But I digress. What we need to know about Merkle-Patricia Tries is as follows:

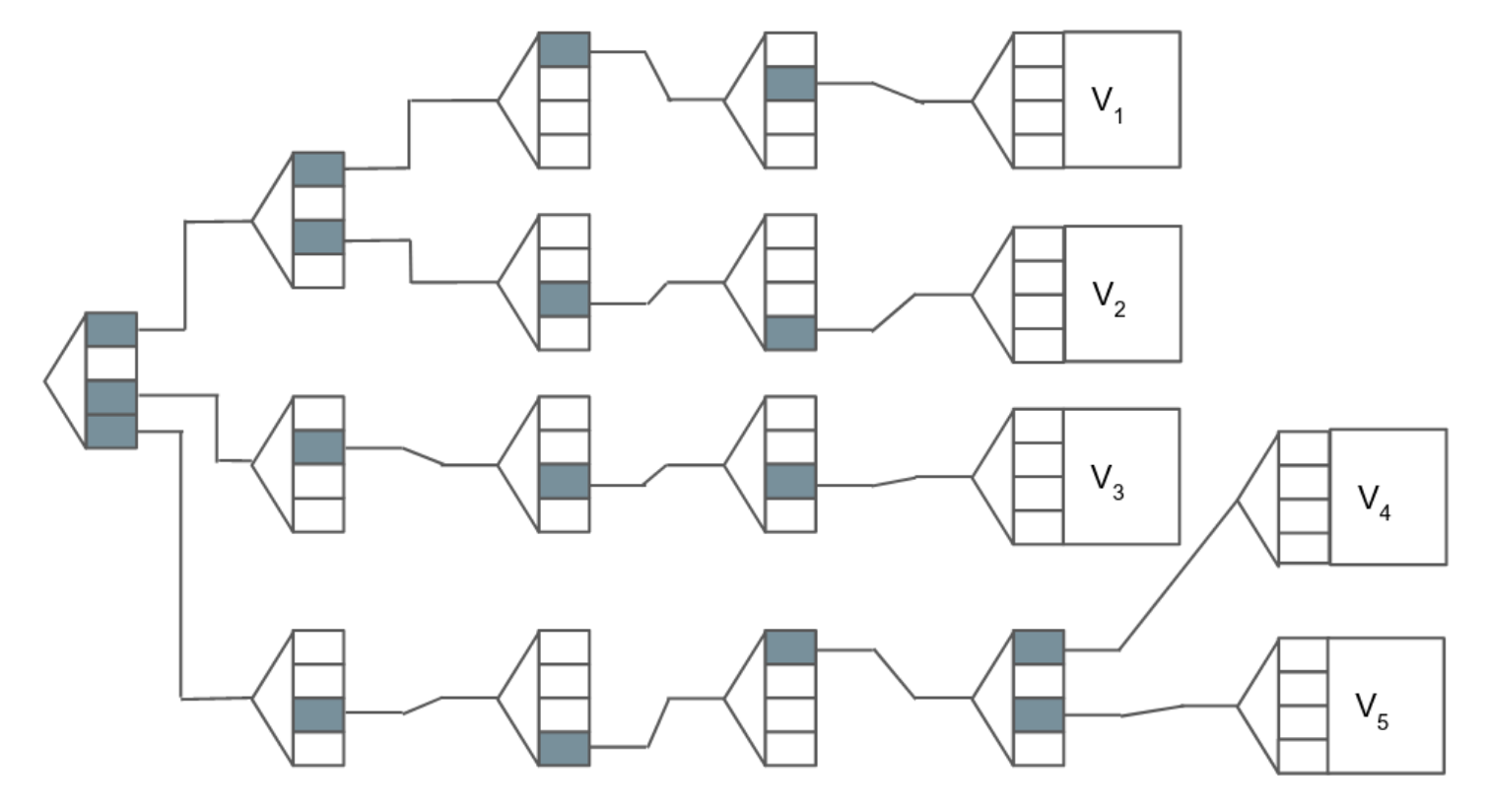

At one end of the trie, there are all of the particular pieces of data that describe state (value nodes). This could be a particular account’s balance, or a variable stored in a smart contract (such as the total supply of an ERC-20 token). In the middle are branch nodes, which link all of the values together through hashing. A branch node is an array containing the hashes of its child nodes, and each branch node is subsequently hashed and put into the array of its parent node. This successive hashing eventually arrives at a single state root node on the other end of the trie.

In the simplified diagram above, we can see each value, as well as the path that describes how to get to that value. For example, to get to V-2, we traverse the path 1,3,3,4. Similarly, V-3 can be reached by traversing the path 3,2,3,3. Note that paths in this example are always 4 characters in length, and that there is often only one path to take to reach a value.

This structure has the important property of being deterministic and cryptographically verifiable: The only way to generate a state root is by computing it from each individual piece of the state, and two states that are identical can be easily proven so by comparing the root hash and the hashes that led to it (a Merkle proof). Conversely, there is no way to create two different states with the same root hash, and any attempt to modify state with different values will result in a different state root hash.

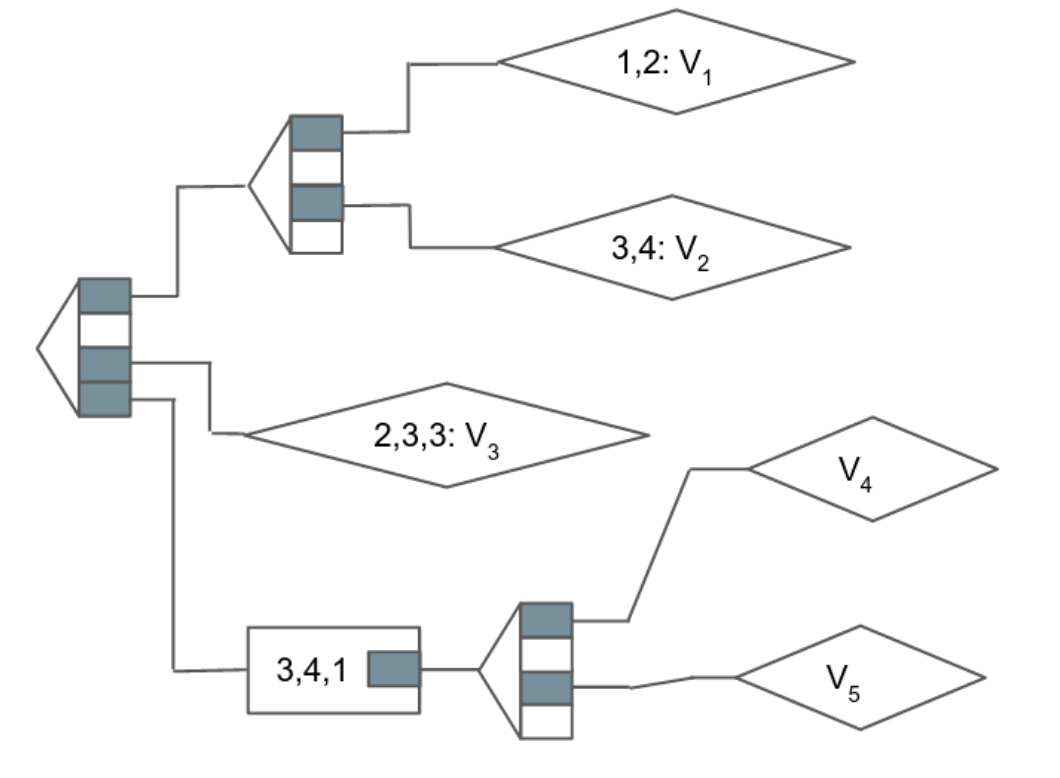

Ethereum optimizes the trie structure by introducing a few new node types that improve efficiency: extension nodes and leaf nodes. These encode parts of the path into nodes so that the trie is more compact.

In this modified Merkle-Patricia trie structure, each node will lead to a choice between multiple next nodes, a compressed part of a path that subsequent nodes share, or values (prepended by the rest of their path, if necessary). It’s the same data and the same organization, but this trie only needs 9 nodes instead of 18. This seems more efficient, but with the benefit of hindsight, isn’t actually optimal. We’ll explore why in the next section.

To arrive at a particular part of state (such as an account’s current balance of Ether), one needs to start at the state root and crawl along the trie from node to node until the desired value is reached. At each node, characters in the path are used to decide which next node to travel to, like a divining rod, but for navigating hashed data structures.

In the ‘real’ version used by Ethereum, paths are the hashes of an address 64 characters (256 bits) in length, and values are RLP-encoded data. Branch nodes are arrays that contain 17 elements (sixteen for each of the possible hexadecimal characters, and one for a value), while leaf nodes and extension nodes contain 2 elements (one partial path and either a value or the hash of the next child node). The Ethereum wiki is likely the best place to read more about this, or, if you would like to get way into the weeds, this article has a great (but unfortunately deprecated) DIY trie exercise in Python to play with.

Stick it in a Database

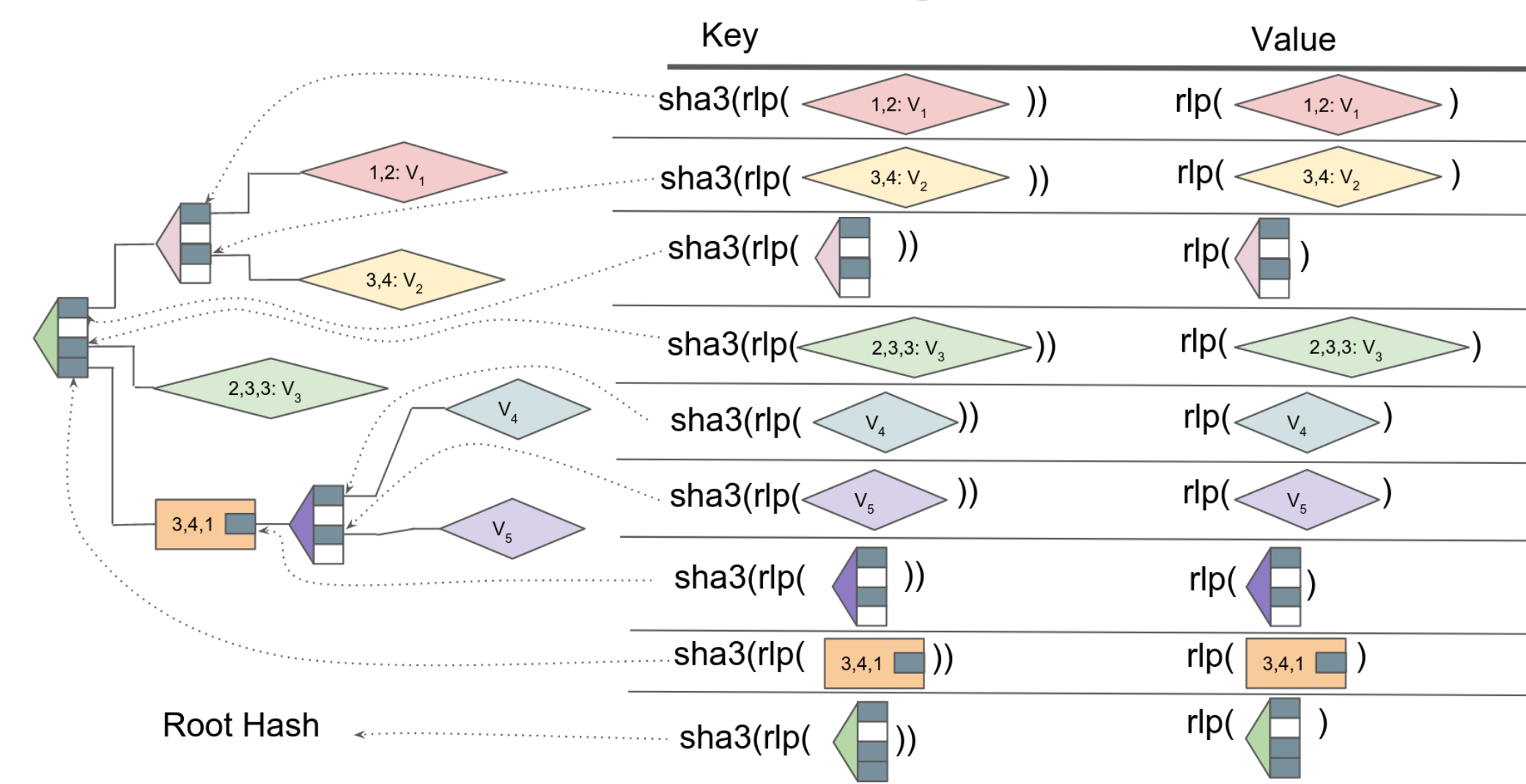

At this point we should remind ourselves that the trie structure is just an abstract concept. It’s a way of packing the totality of Ethereum state into one unified structure. That structure, however, then needs to be implemented in the code of the client, and stored on a disk (or a few thousand of them scattered around the globe). This means taking a multi-dimensional trie and stuffing it into an ordinary database, which understands only (key, value) pairs.

In most Ethereum clients (all except turbo-geth), the Merkle-Patricia Trie is implemented by creating a distinct (key, value) pair for each node, where the value is the node itself, and the key is the hash of that node.

The process of traversing the trie, then, is more or less the same as the theoretical process described earlier. To look up an account balance, we would start with the root hash, and look up its value in the database to get the first branch node. Using the first character of our hashed address, we find the hash of the first node. We look that hash up in the database, and get our second node. Using the next character of the hashed address, we find the hash of the third node. If we’re lucky, we might find an extension or leaf node along the way, and not need to go through all 64 nibbles — but eventually, we’ll arrive at our desired account, and be able to retrieve its balance from the database.

Computing the hash of each new block is largely the same process, but in reverse: Starting with all the edge nodes (accounts), the trie is built through successive hashings, until finally a new root hash is built and compared with the last agreed-upon block in the chain.

Here’s where that bit about the apparent efficiency of the state trie comes into play: re-building the whole trie is very intensive on disk, and the modified Merkle-Patricia trie structure used by Ethereum is more protocol efficient at the cost of implementation efficiency. Those extra node types, leaf and extension, theoretically save on memory needed to store the trie, but they make the algorithms that modify the state inside the regular database more complex. Of course, a decently powerful computer can perform the process at blazing speed. Sheer processing power, however, only goes so far.

Sync, baby, sync

So far we’ve limited our scope to what’s going on in an individual computer running an Ethereum implementation like geth. But Ethereum is a network, and the whole point of all of this is to keep the same unified state consistent across thousands of computers worldwide, and between different implementations of the protocol.

The constantly shuffling tokens of #Defi, cryptokitty auctions or cheeze wizard battles, and ordinary ETH transfers all combine to create a rapidly changing state for Ethereum clients to stay in sync with, and it gets harder and harder the more popular Ethereum becomes, and the deeper the state trie gets.

Turbo-geth is one implementation that gets to the root of the problem: It flattens the trie database and uses the path of a node (rather than its hash) as the (key, value) pair. This effectively makes the depth of the tree irrelevant for lookups, and allows for a variety of nifty features that can improve performance and reduce the load on disk when running a full node.

The Ethereum state is big, and it changes with every block. How big, and how much of a change? We can ballpark the current state of Ethereum at around 400 million nodes in the state trie. Of these, about 3,000 (but as many as 6,000) need to be added or modified every 15 seconds. Staying in sync with the Ethereum blockchain is, effectively, constantly building a new version of the state trie over and over again.

This multi-step process of state trie database operations is why Ethereum implementations are so taxing on disk I/O and memory, and why even a “fast sync” can take up to 6 hours to complete, even on fast connections. To run a full node in Ethereum, a fast SSD (as opposed to a cheap, reliable HDD) is a requirement, because processing state changes is extremely demanding on disk read/writes.

Here it’s important to note that there is a very large and significant distinction between establishing a new node to sync and keeping an existing node synced — A distinction that, when we get to stateless Ethereum, will blur (hopefully).

The straightforward way to sync a node is with the “full sync” method: Starting from the genesis block, a list of every transaction in each block is retrieved, and a state trie is built. With each subsequent block, the state trie is modified, adding and modifying nodes as the complete history of the blockchain is replayed. It takes a full week to download and execute a state change for every block from the beginning, but it’s just a matter of time before the transactions you need are pending inclusion into the next new block, rather than being already solidified in an old one.

Another method, aptly named “fast-sync”, is quicker but more complicated: A new client can, instead of requesting transactions from the beginning of time, request state entries from a recent, trusted ‘checkpoint’ block. It’s far less total information to download, but it is still a lot of information to process– sync is not currently limited by bandwidth, but by disk performance.

A fast-syncing node is essentially in a race with the tip of the chain. It needs to get all of the state at the ‘checkpoint’ before that state goes stale and stops being offered by full nodes (It can ‘pivot’ to a new checkpoint if that happens). Once a fast-syncing node overcomes the hurdle and get its state fully caught up with a checkpoint, it can then switch to full sync — building and updating its own copy of state from the included transactions in each block.

Can I get a block witness?

We can now start to unpack the concept of stateless Ethereum. One of the main goals is to make new nodes less painful to spin up. Given that only 0.1% of the state is changing from block to block, it seems like there should be a means of cutting down on all that extra ‘stuff’ that needs to be downloaded before the full sync switchover.

But this is one of the challenges imposed by Ethereum’s cryptographically secure data structure: In a trie, a change to just one value will result in a completely different root hash. That’s a feature, not a bug! It keeps everybody certain that they are on the same page (at the same state) with everyone else on the network.

To take a shortcut, we need a new piece of information about state: a block witness.

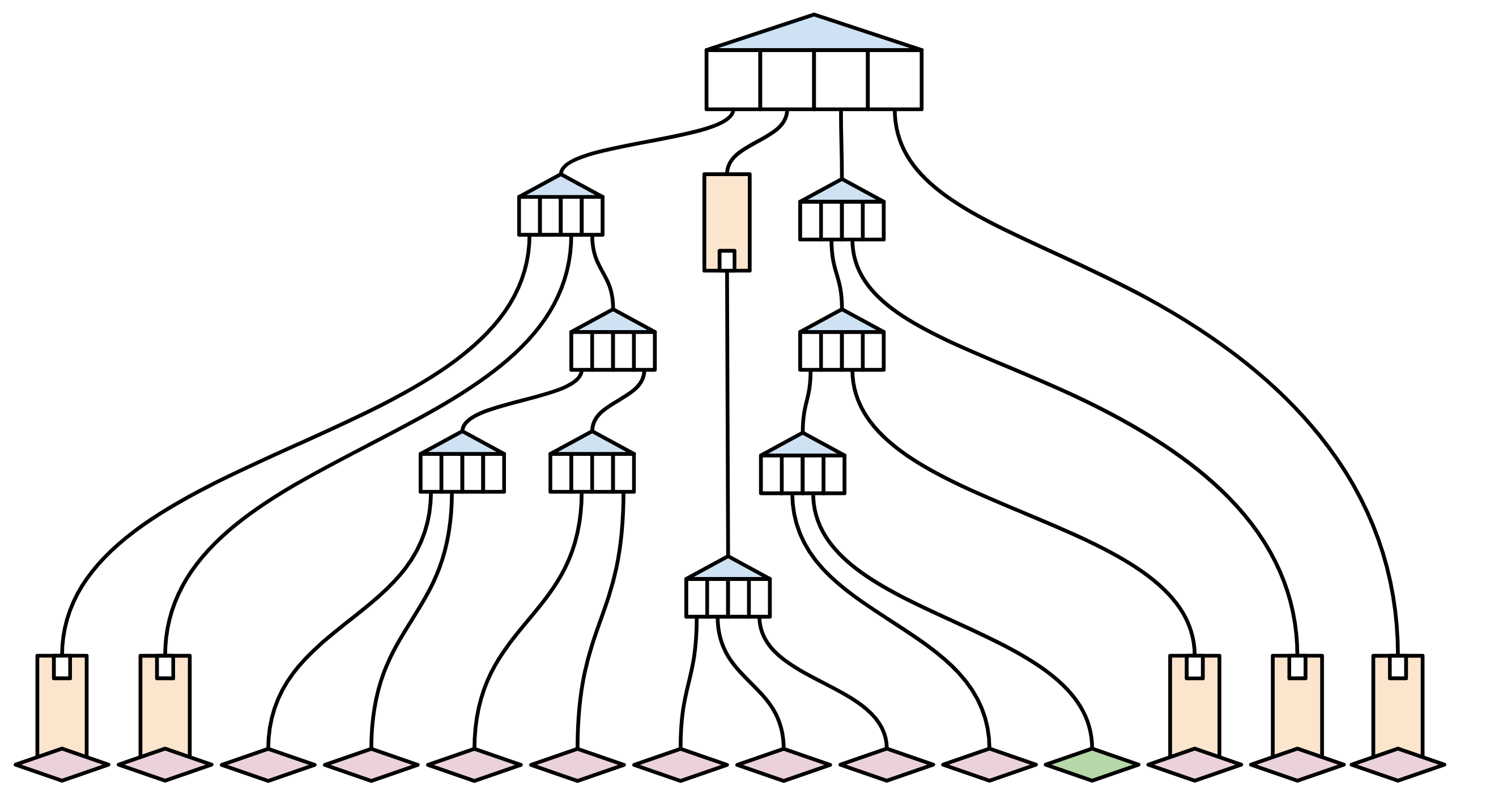

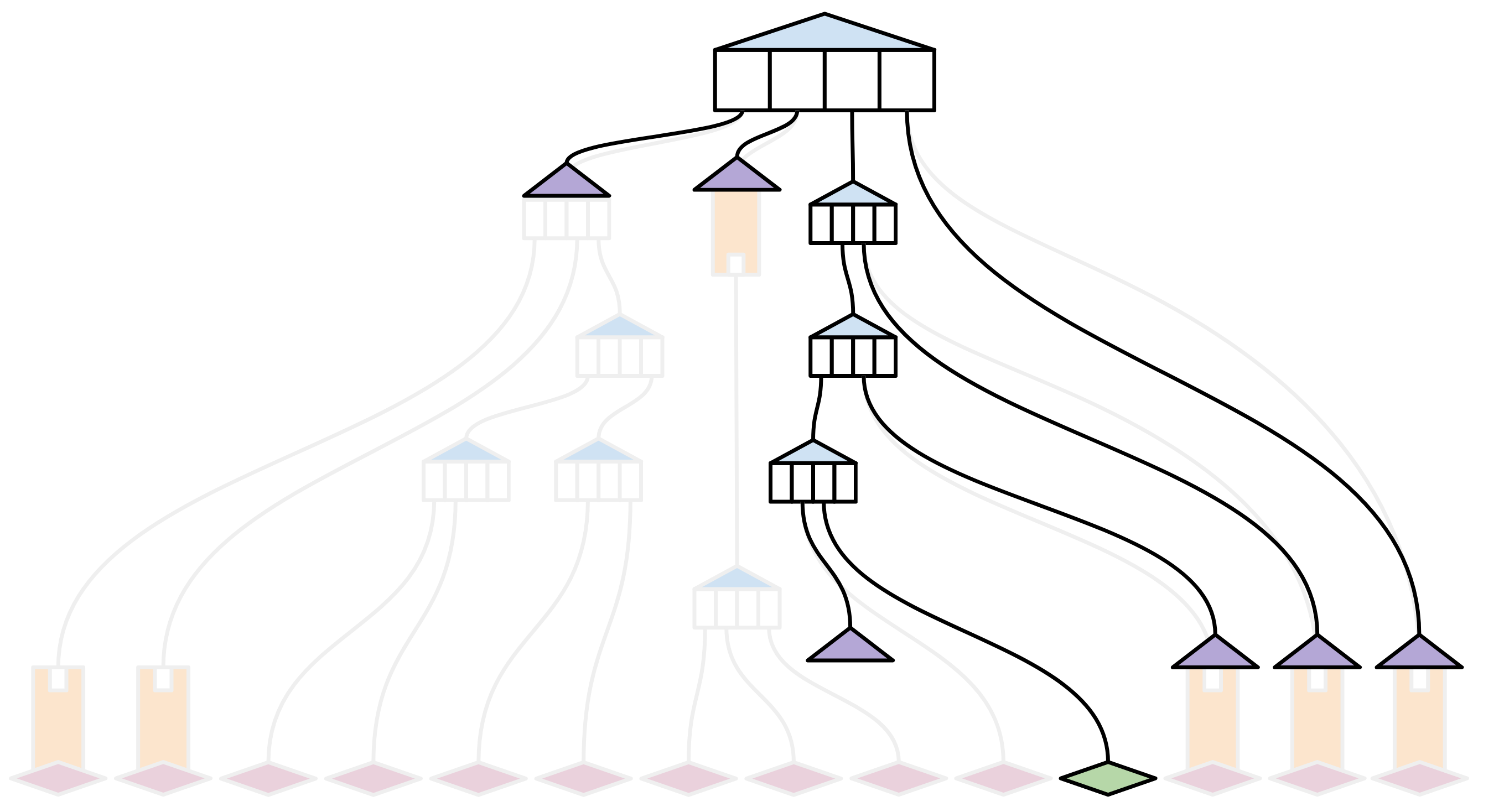

Suppose that just one value in this trie has changed recently (highlighted in green):

A full node syncing the state (including this transaction) will go about it the old-fashioned way: By taking all the pieces of state, and hashing them together to create a new root hash. They can then easily verify that their state is the same as everyone else’s (since they have the same hash, and the same history of transactions).

But what about someone that has just tuned in? What’s the smallest amount of information that new node needs in order to verify that — at least for as long as it’s been watching — its observations are consistent with everyone elses?

A new, oblivious node will need older, wiser full nodes to provide proof that the observed transaction fits in with everything they’ve seen so far about the state.

In very abstract terms, a block witness proof provides all of the missing hashes in a state trie, combined with some ‘structural’ information about where in the trie those hashes belong. This allows an ‘oblivious’ node to include the new transaction in its state, and to compute the new root hash locally — without requiring them to download an entire copy of the state trie.

This is, in a nutshell, the idea behind beam sync. Rather than waiting to collect each node in the checkpoint trie, beam sync begins watching and trying to execute transactions as they happen, requesting a witness with each block from a full node for the information it doesn’t have. As more and more of the state is ‘touched’ by new transactions, the client can rely more and more on its own copy of state, which (in beam sync) will gradually fill in until it eventually switches over to full sync.

Statelessness is a spectrum

With the introduction of a block witness, the concept of ‘fully stateless’ starts to get more defined. At the same time, it’s where we start to run into open questions and problems with no obvious solution.

In contrast to beam sync, a truly stateless client would never keep a copy of state; it would only grab the latest transactions together with the witness, and have everything it needs to execute the next block.

You might see that, if the entire network were stateless, this could actually hold up forever– witnesses for new blocks can be produced from the previous block. It’d be witnesses all the way down! At least, down to the last agreed upon ‘state of affiars’, and the first witness generated from that state. That’s a big, dramatic change to Ethereum not likely to win widespread support.

A less dramatic approach is to accommodate varying degrees of ‘statefullness’, and have a network in which some nodes keep a full copy of the state and can serve everyone else fresh witnesses.

-

Full-state nodes would operate as before, but would additionally compute a witness and either attach it to a new block, or propagate it through a secondary network sub-protocol.

-

Partial-state nodes could keep a full state for just a short number of blocks, or perhaps just ‘watch’ the piece of state that they’re interested in, and get the rest of the data that they need to verify blocks from witnesses. This would help infrastructure-running dapp developers immensely.

-

Zero-state nodes, who by definition want to keep their clients running as light as possible, could rely entirely on witnesses to verify new blocks.

Getting this scheme to work might entail something like bittorrent-style chunking and swarming behavior, where witness fragments are propagated according to their need and best connections to other nodes with (complementary) partial state. Or, it might involve working out an alternative implementation of the state trie more amenable to witness generation. This is stuff to investigate and prototype!

For a much more in-depth analysis of what the trade-offs of stateful vs stateless nodes are, see Alexey Akhunov’s The shades of statefulness.

An important feature of the semi-stateless approach is that these changes don’t necessarily imply big, hard-forking changes. Through small, testable, and incremental improvements, it’s possible to build out the stateless component of Ethereum into a complementary sub-protocol, or as a series of un-controversial EIPs instead of a large ‘leap-of-faith’ upgrade.

The road(map) ahead

The elephant in the research room is witness size. Ordinary blocks contain a header, and a list of transactions, and are on the order of 100 kB. This is small enough to make the propagation of blocks quick relative to network latency and the 15 second block time.

Witnesses, however, need to contain the hashes of nodes both at the edges and deep inside the state trie. This means they are much, much bigger: early numbers suggest on the order of 1 MB. Consequently, syncing a witness is much much slower relative to network latency and block time, which could be a problem.

The dilemma is akin to the difference between downloading a movie or streaming it: If the network is too slow to keep up with the stream, downloading the full movie is the only workable option. If the network is much faster, the movie can be streamed with no problem. In the middle, you need more data to decide. Those with sub-par ISPs will recognize the gravity of attempting to stream a friday night movie over a network that might not be up for the task.

This, largely, is where we start getting into the detailed problems that the Eth 1x group is tackling. Right now, not enough is known about the hypothetical witness network to know for sure it’ll work properly or optimally, but the devil is in the details (and the data).

One line of inquiry is to think about ways to compress and reduce the size of witnesses by changing the structure of the trie itself (such as a binary trie), to make it more efficient at the implimentation level. Another is to prototype the network primitives (bittorrent-style swarming) that allow witnesses to be efficiently passed around between different nodes on the network. Both of these would benefit from a formalized witness specification — which doesn’t exist yet.

All of these directions (and more) are being compiled into a more organized roadmap, which will be distilled and published in the coming weeks. The points highlighted on the roadmap will be topics of future deep dives.

If you’ve made it this far, you should have a good idea of what “Stateless Ethereum” is all about, and some of the context for emerging Eth1x R&D.

As always, if you have questions about Eth1x efforts, requests for topics, or want to contribute, come introduce yourself on ethresear.ch or reach out to @gichiba and/or @JHancock on twitter.

Special thanks to Alexey Akhunov for providing technical feedback and some of the trie diagrams.

Happy new year, and happy Muir Glacier hardfork!