The Beginning of a New Regime: Implications for Bonds

Andriy Yalansky

Written by Scott DiMaggio, Michael Rosborough, Fahd Malik

What does an era of high equilibrium inflation mean for yields, volatility, and active bond investing?

Over the past 40 years, global deflationary factors have prevailed, promoting a low interest rate regime. Balance inflation. But change is happening. Increasing pressure from macro forces suggests higher structural inflation and lower real GDP growth in the coming years. We believe that higher inflation and slower economic growth will have an impact across global bond markets and shape how investors allocate capital over the long term. In our view, this new regime will be informed by slow rollouts rather than seismic changes. In reality, it’s likely already arrived. Here’s how we expect things to unfold over the next 10 years.

higher and higher inflation

We believe we have entered a regime where: Structural inflation will rise, but we will be more vulnerable to inflationary shocks. Three powerful forces are at the core of our expectations of higher equilibrium inflation. Deglobalization, demography and climate change.

- Deglobalization leads, among other things, to limiting the global labor pool and increasing the bargaining power of the labor force, leading to higher inflation. Anti-globalization also puts downward pressure on GDP growth.

- Meanwhile, the global workforce is shrinking due to an aging population. Without sustained increases in productivity to offset this, a shrinking labor force not only hinders economic growth but also gives the workforce more bargaining power. This is another factor in inflation.

- The inflationary effects of deglobalization and demography could be further exacerbated by climate change. For example, the energy transition may be deflationary in the long run, but it may also lead to higher costs over the next decade.

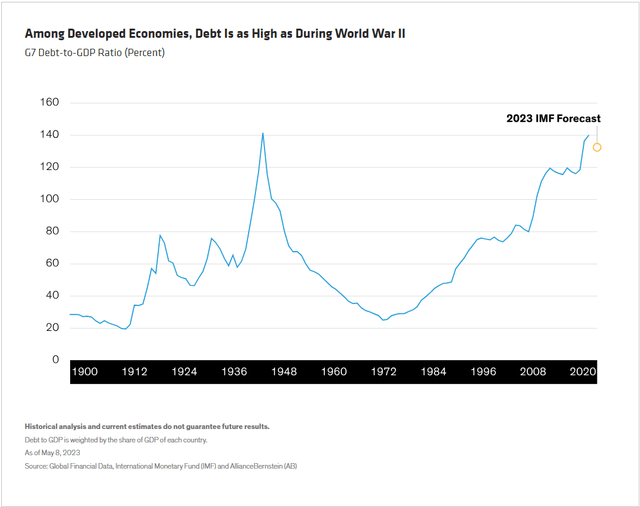

Of course, deflationary factors continue to operate. For example, technology has been experiencing deflation for many years and is likely to continue to do so. The evidence for this is not yet visible in aggregate statistics, but we can see productivity gains through generative artificial intelligence. The combined forces of inflation and deflation imply a shift in the balance of power between capital and labor, leading to a higher equilibrium inflation level, with 2% being the lower bound rather than the target. In fact, it is likely that we have already entered this new regime, although recent cyclical inflation peaks have obscured the evidence for this. That said, more frequent spikes in inflation may be a feature of the new regime. That’s because today’s massive government debt levels incentivize policymakers to inflate and eliminate debt. Debt-to-GDP ratios in developed countries today are as high as they were during World War II, when the previous record was broken.Denote). Until now, this massive increase in public debt has been of little consequence. Because the cost of debt was so low.

Now that the cost of debt has risen, the story is different. Debt management likely involves running nominal GDP (real GDP + inflation) above the cost of debt. And if real GDP is expected to slow (which we think it will), inflation becomes not only acceptable but crucial to reducing the overall debt burden. At the same time, policymakers have expressed a strong preference for avoiding deflation as they look to emerge from the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. As Japan demonstrates, deflation is incredibly difficult to overcome. To prepare for this, policymakers tend to aggressively deploy fiscal expansion and interest rate cuts, leading to over-adjustment in the form of rising inflation. In our view, higher tolerance for intermittent inflation spikes beyond already higher equilibrium levels is likely.

Higher nominal interest rates and steeper yield curves

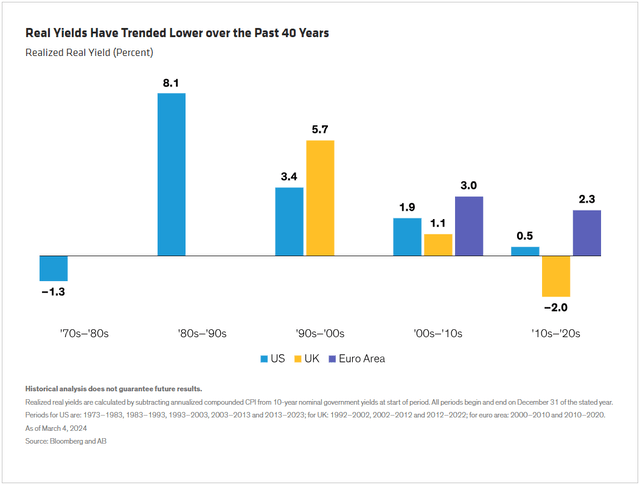

If long-term inflation is higher, nominal interest rates are likely to be higher over the next decade. Since nominal returns are comprised of inflation and real returns, the question arises as to whether real returns will remain as low as they have been over the past 20 years.Denote).

We think they can. On the one hand, now that quantitative easing is over, real yields are unlikely to turn negative again. Over the past decade, average real rates of return have been too low to keep pace with GDP growth. On the other hand, real returns should be limited by (more moderate) real economic growth in the long run. Our analysis therefore suggests that real returns may be trending in line with realized real returns in the decade preceding the global financial crisis. Higher inflation means higher nominal returns, but higher inflation means higher nominal returns. volatility This means the yield curve is steeper. Over the past decade, term insurance premiums have largely disappeared. Over the next decade, we believe term premiums will increase to compensate investors for the risk of holding long-term bonds in an environment where inflation expectations are less certain. Supply constraints may keep the long end of the yield curve higher than it has been in the recent past.

Active management could make a comeback

Higher interest rates generally result in higher interest rate volatility. As a result, higher volatility means greater dispersion and confusion. This means that return patterns across regions, sectors and industries become more diverse, creating greater challenges and more unusual opportunities. Both active and passive strategies play an important role in investors’ portfolios, but more volatile environments favor active managers who can leverage new methods for diversification, increased opportunities to add alpha, and the ability to maneuver to avoid problem spots. . As a result, we expect to see a resurgence in active strategies over the next decade.

Explicit inflation protection needed

In the face of higher inflation and more frequent inflation spikes, investors are also expected to place greater emphasis on inflation strategies. This includes explicit inflation protection in the form of inflation-linked securities, known outside the U.S. as “linkers” and in the U.S. as Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). Now may be a particularly good time to buy TIPS. TIPS, like other Treasury securities, are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. They are designed to fully compensate investors for inflation and also provide protection against deflation when newly issued. In other words, inflation compensation is not negative. And today, investors can purchase TIPS whose annual returns could approach U.S. economic growth over the next decade. In the 27 years since TIPS was first launched, TIPS has averaged 90 basis points below GDP growth. This isn’t the only metric that makes TIPS’s price look attractive. The current 10-year breakeven rate (the yield difference between 10-year nominal Treasury bonds and 10-year TIPS and the implicit market forecast for CPI over the next 10 years) is 2.30%. An analysis of historical inflation measures since TIPS first hit the market 27 years ago suggests that a fair breakeven point should be 2.51%. That said, TIPS are unusually cheap in many ways, so investors should now consider increasing their allocations.

Investors can return to natural habitat

After more than two decades of unusually low interest rates and under-allocation to bonds, a new regime of higher equilibrium inflation, higher nominal yields, and higher volatility could reshape how investors allocate capital over the long term. Institutional investors may want to rethink the long-term assumptions they use to allocate assets. The way we think about risk is also likely to change. Many investors have been focused on hedging against 2008-type credit distress. But inflation is likely to be the biggest risk we need to prepare for in the coming years, as it has been in the past. In our view, this is not a reason to avoid fixed income. Rather, with allocations to active bonds and explicit inflation strategies playing a larger role than in recent years, many investors may find themselves back in familiar territory when it comes to allocating to bonds.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trading recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of the entire AB Portfolio Management team. Views may change over time.

original post

Editor’s note: The summary bullet points for this article were selected by Seeking Alpha editors..